A few years back, when I lived in Brooklyn, I cared for a colony of feral cats. I trapped and neutered them, set up a feeding station in my backyard, and, like a wildlife researcher, watched with fascination from my window as they lived their reclusive lives. One of my favorites in the gang was Mr. Big. He was the alpha. The cat everyone would sit and wait for to finish eating before they swooped in for their own servings.

I fell in love with him when he took a liking to a lonely young lass (remember, everyone’s fixed here) who was sneaking into the garden to eat whatever leftovers were left behind. I would often find them sunning together, and despite the tension it created amongst the other cats, Mr. Big would stand guard while she got her fair share of food; giving the stink eye to any of his minions who thought to push her out of the way. There was just something so sweet about this gesture. If I ever saw the little lady alone, I would ask her where her boyfriend was only to have him come around the corner and rub up against her to let me know he had her back.

On the anniversary of Bruce and my 1st date, while walking home from the taqueria we met at, I found Mr. Big’s cold body on the sidewalk. He had been hit by a car. Someone had placed a sheet over his body, but his tail stuck out, as if to flag me down and say, “Don’t leave me here.” I got the car, gently put his body next to me in the passenger seat, and drove to my local vet ER to ask them to cremate him for me. I was devastated. Why, with food and friends always outside my back door, had this guy tried to travel across the street?

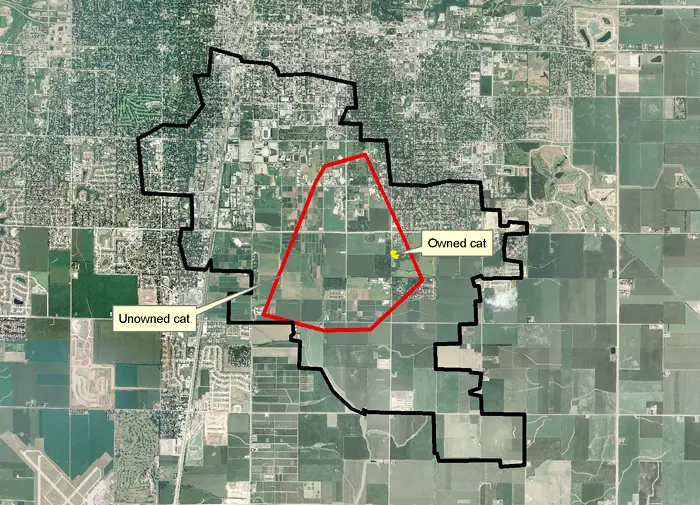

While I’ll never know why he left the comfort of our block’s backyards, new research shows us just how far both feral and pet cats travel when they’re outdoors. Scientists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign outfitted 42 adult felines with radio transmitters that transmitted data on where they were going. Twenty-three of the transmitters had tilt and vibration sensors that tracked the kitties actual movements. The data was collected for two years, giving some of the most comprehensive information on cat territory and activities.

The feral cats, not surprisingly, had some of the largest territories, including one tom who kept watch on 1,351 acres (two square miles) that ranged from rural fields, forests and prairies to urban residential and campus sites.

“That particular male cat was not getting food from humans, to my knowledge, but somehow it survived out there amidst coyotes and foxes,” Jeff Horn, a former University of Illinois graduate student who conducted the study for his master’s thesis told the Illinois New Bureau. “It crossed every street in the area where it was trapped. [It navigated] stoplights, parking lots. We found it denning under a softball field during a game.” No information was given on whether the cats were fixed or not, which I would assume would affect roaming to a certain degree.

The owned cats, naturally, had smaller territories, but still rather large – the mean being 4.9 acres.

There was also a vast difference in activity levels between both types of cats. The ferals were highly active for 14% of their time, while pet cats were active for only 3%. I suspected as much since I often found my own cats, when they were allowed outside, sunning themselves in people’s yards rather than exploring.

Images: Illinois Natural History Survey